Children’s books should be age-appropriate

On the proliferation of queer books for elementary readers

Recently, I bought my son a Minecraft comic book about a group of kids who team up to fight the ender dragon. Right in the middle of the adventure, one of the girls confesses her crush on her female friend:

My son had no reaction. He just looked bored until we got back to the action. I wouldn’t call the lesbian subplot inappropriate, but it took me out of the story because it seemed to be wedged in to make a political point. So I was unsurprised to learn the author identifies as trans, queer, and nonbinary (they/them).

It’s part of a trend I’m seeing everywhere: Queer, childfree authors churning out children’s books with content that isn’t relatable or appropriate for the target audience.

“This is the extent of anything remotely sexual.”

The excellent book Stolen Youth alerted me to The Breakaways, a graphic novel for elementary school students (ages 8-11 according to the publisher) which features a sexy bedroom scene.

One girl tells the other “I think I’m a boy,” and they make out in bed. These characters are in middle school, and we’re supposed to buy the book for eight-year-olds.

A few districts removed1 the book from elementary school libraries, prompting accusations of literal genocide. A “parent of two non-binary children” told ABC News: "It makes us feel attacked, especially my children feeling attacked. That their existence, their humanity, is being erased.”

Richard Price, who runs a website on censorship, argues that the above scene isn't sexual:

This is the extent of the “sexual conduct” seen in the book. Two kids are sharing a bed during a sleepover when one comes out as trans and asks to kiss his best friend. They later start dating. This is the extent of anything remotely sexual. Middle grade books regularly depict kids kissing because, shockingly, kids kiss. The only thing objectionable here, to the challengers and apparently censors at the school, is one kid is trans.

Imagine you walked into your daughter’s room and caught her in bed with a classmate, embracing and making out. Would you think to yourself, “Oh good, I’m glad they’re not doing anything sexual” and head downstairs? No, you would have some fucking concerns.

Whatever you think about gender and sexual orientation, nothing justifies a steamy bedroom scene for eight-year-olds.

Gender = regressive stereotypes

In The Breakaways, the character’s announcement (“I know I’m a boy”) is met with unquestioning acceptance. Nobody asks, “What do you mean by that?” which must be confusing to young readers.

But to be fair, it’s so much worse when they explain.

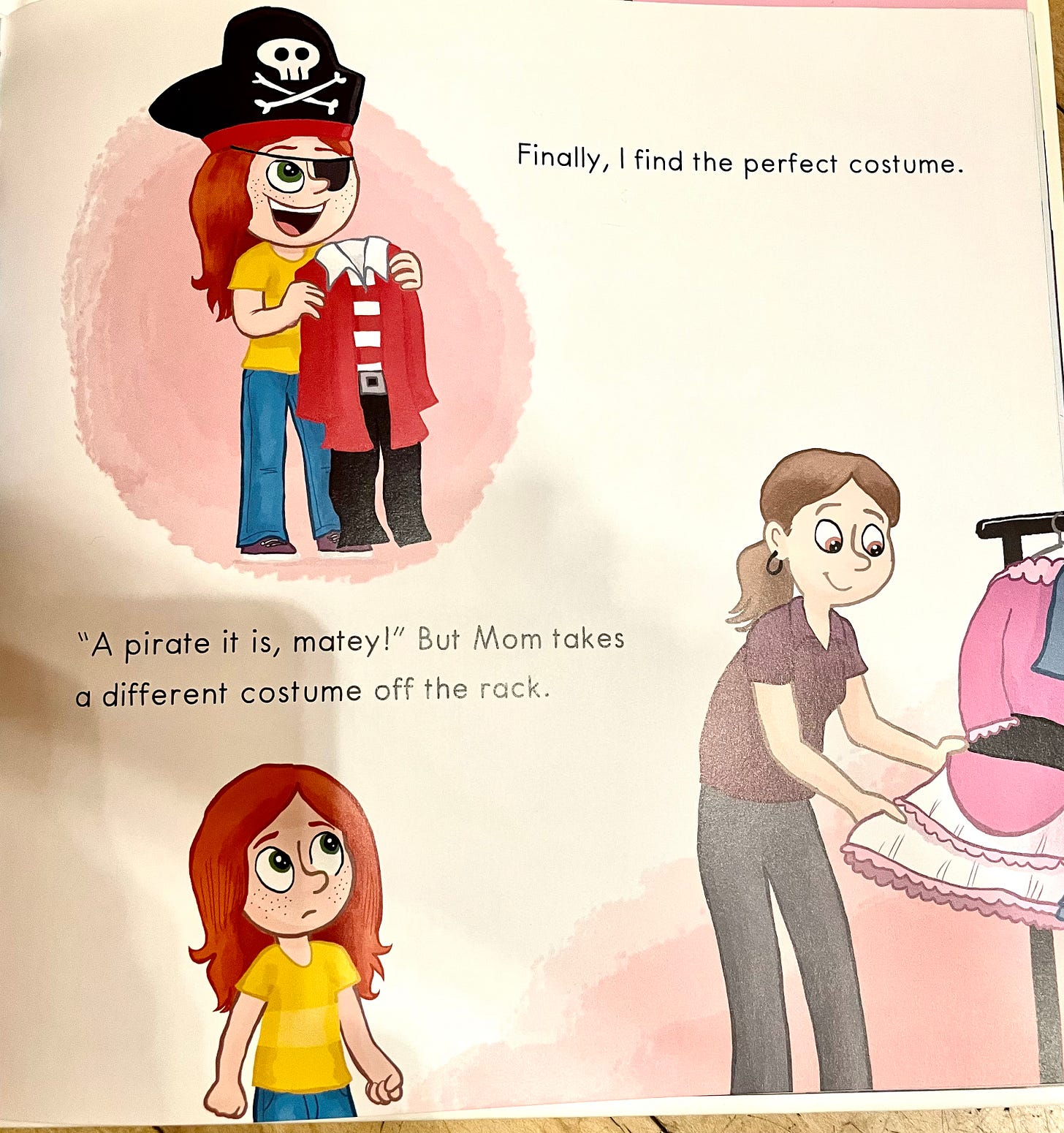

I’m Not a Girl is a picture book about a child who realizes she’s actually a boy because she 1) Wants to be a pirate for Halloween, 2) Dislikes pink dresses, and 3) Prefers short hair.

You see, only boys like pirates and short hair. Girls wear frilly dresses and shun adventure. It’s delightful to live in this enlightened age.

The recommended age range for I’m Not a Girl is 3-6. Which is interesting because my son was three when he told me one time, “I’m a girl.”

A woke, liberal mom might have jumped on his statement with starry eyes and frothing lips. “OMG, you’re a girl?? Really?? Would you like to pick a new name??” Kids love positive attention, so it’s easy to imagine a manic escalation lasting months or even years.

I just said, “Oh really? Okay,” as though he’d told me “I’m a dinosaur.” He never mentioned it again, and he continues to be a typical, gender-conforming boy.2

His comment didn’t mean anything because he was three.

Appropriate representation

It’s good to normalize gay relationships, because children will encounter gay people in the world. Some of their friends (like my son) have same-sex parents. And yes, some kids will grow up to be gay.

But positive representation can be accomplished without pushing young children to adopt a queer (or straight) identity when they shouldn’t even be thinking about attraction or dating.

Personally, I like books that portray gay people as frumpy, boring parents. They teach children gay people exist, and we’re just like anyone else.

Will young Heather grow up to be lesbian? Nobody knows or cares. But if you present lesbian couples as normal, happy adults, your kids won’t be afraid if they have a same-sex crush one day.

As for gender, I like books where girls go on adventures and boys can play with anything they like. Children need unconditional acceptance, not boxes and labels.

Older children read about crushes and dating, and it’s fine to show same-sex dating in middle-grade books. But the same rules should apply. If you wouldn’t show a straight girl in bed with a straight boy—and get real, you would not—it’s just as inappropriate when the kids are “queer.”

Childfree authors

The proliferation of age-inappropriate rainbow books reflects a few trends in our society: The explosion of lgbtq+++ identities, the plummeting birth rate, and the number of humanities majors seeking creative work wherever they can find it.

It’s not a coincidence that, as far as I can tell, most of the authors don’t have children.3 While there are exceptions, many (queer, creative) childfree adults seem to identify with kids more than parents, and this warps their sense of what is appropriate.

I’m not saying books should carry a special sticker to indicate the author has four pronouns and zero kids. I’m just saying an actual parent should read these books before you shelve them in a kindergarten classroom.

It’s silly to call this a “book ban” when the issue is whether it should be offered in an elementary school library. Is Hustler Magazine banned because elementary schools don’t subscribe? When the audience is children, who are legally required to be there, some curation should be expected.

As lesbians, we were ready to embrace our son’s gender non-conforming interests, but it turns out he hardly has any. He spent covid-19 surrounded by women and still came out obsessed with trucks, construction, and dinosaurs. 🤷🏻♀️

The exception is Jessica Verdi, a co-author of “I’m Not a Girl”—but the other author is a 12-year-old “transgender boy” who provided the story. Cathy G. Johnson, Sfé R. Monster, and Richard Price don’t mention children in their bios.

Tee hee: “four pronouns and zero kids.” You make an excellent point--which I haven’t seen anyone else make before--that childless authors will have trouble understanding the concept of age-appropriateness, especially when they have a political agenda.

I was convinced of a similar point by a friend who is an Orthodox Jew and the child of Holocaust survivors and yet publicly supported the removal of Maus from the middle-school curriculum. He has a son, and he has written that Maus is not appropriate for middle schoolers, because it is unrelentingly bleak and extremely violent. Better for kids to read the book when they’re a bit older and better able to understand and absorb the ideas in the book.

I think we parents ought to keep making this point--that wanting kids to read book when they are ready for them, and not prematurely, is not the same thing as censorship, and still less genocide. It’s good parenting and teaching.

I remember seeing something on social media about a dad's struggle with his child adopting a transgender identity. A childless progressive responded with something to the effect of "imagine hating your kid because trans people exist".

I'm a childless adult too, so I can't claim any wisdom here. But I can at least kind of imagine the the emotions that might run through a father's head in that scenario.

I think the phenomenon of childlessness and it's effects are really intriguing topics I'd like to see explored. I talk to a lot of professional class women and so many don't want kids. I'm talking women in their late 20s and early 30s.

I never considered your point of the authors relating more to the child than the parent. It might explain a lot about the issue